The Geography of the Self | Review of The Black Book of Power by Stan Taylor

A review by someone who has spent a lifetime mapping external territories while ignoring the one that mattered most.

I have spent twenty-three years writing about places most people will never visit. I have chronicled the night markets of Chiang Mai, the salt flats of Bolivia, and the forgotten railway towns of Kazakhstan. I have made a career of describing the unfamiliar, of translating foreign landscapes into prose that makes readers feel they have walked those streets themselves. I was, by most measures, successful at this work. What I did not understand until eighteen months ago was that I had chosen this profession precisely because it allowed me to remain a permanent outsider that is always observing, never observed, and perpetually in transit between places that were never quite home.

The revelation arrived not in some remote village but in a Holiday Inn Express outside of Tulsa, Oklahoma, where I had stopped on a drive from Dallas to nowhere in particular. I was fifty-four years old, twice divorced, and scrolling through my phone at because sleep had become something that happened to other people. An advertisement appeared. The copy was aggressive in a way that felt almost rude. Something about being a "walking dead" person living someone else's script. I would normally scroll past such things. Instead, I read the free chapter, and then I purchased the book, and then I did not sleep at all that night because I was too busy recognizing myself on every page.

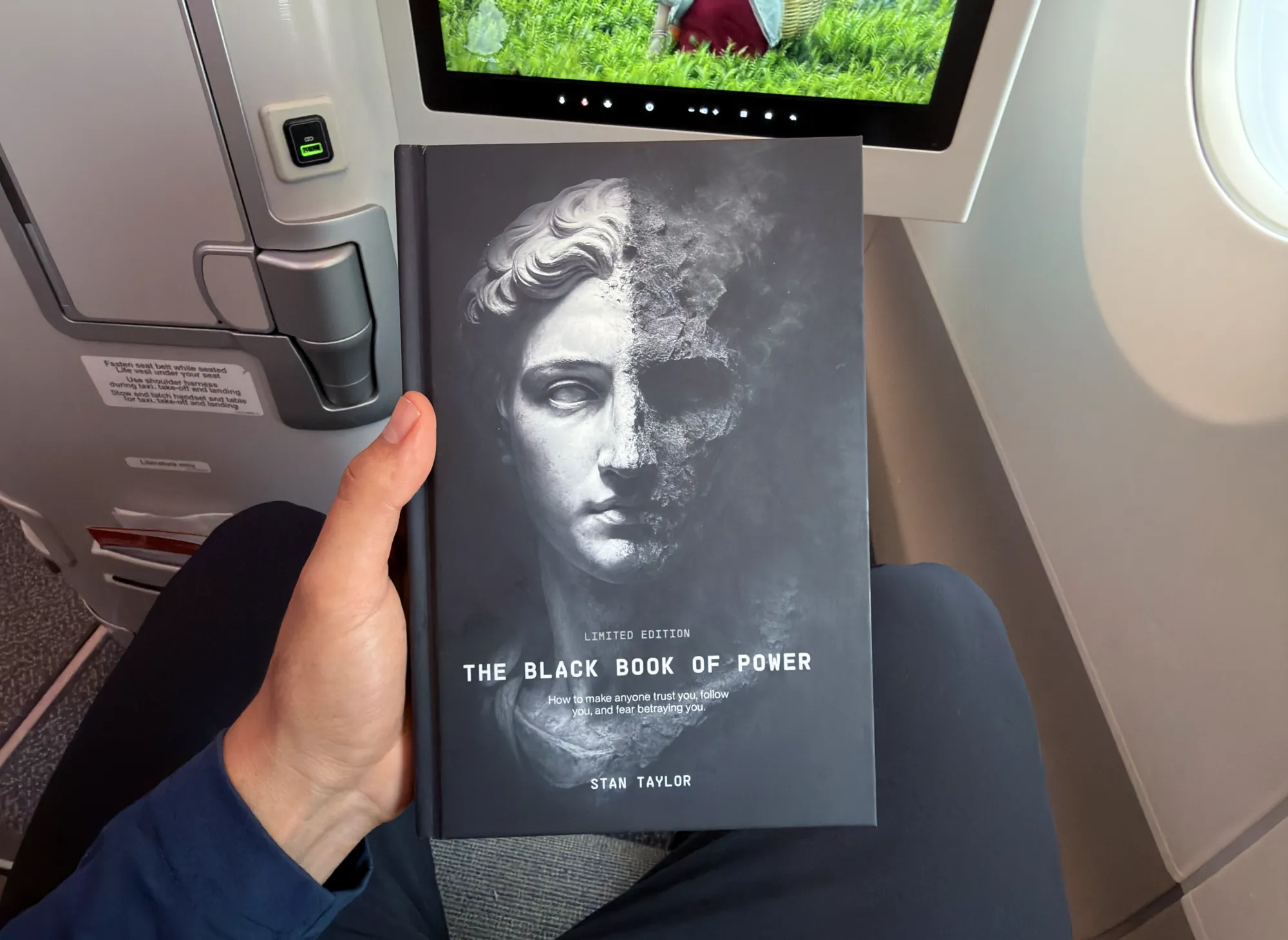

This is not a comfortable review to write. The book in question—Stan Taylor's The Black Book of Power—is not a comfortable book to read. It is also not what its title suggests to the casual browser. When I first saw the cover, I assumed it was another entry in the long tradition of Machiavellian self-help, the kind of book that promises to teach you how to dominate boardrooms and manipulate romantic partners. I was wrong. The book does contain frameworks for influence, sophisticated ones that I suspect actually work. But these frameworks arrive in Parts III, IV, and V, and the author has constructed the text so that reaching them without completing Part II is not merely inadvisable but genuinely dangerous. This architectural choice is, I have come to believe, the book's most important feature.

Let me explain what I mean by describing my own passage through it.

Part I: The Diagnosis

The first three chapters function as what Taylor calls a "system diagnostic." They are designed to show you, with uncomfortable precision, the degree to which your thoughts, beliefs, and behaviors are not your own. Chapter One introduces the concept of "Factory Settings"—the operating system installed during childhood that continues to run your psychology decades later. Taylor identifies three primary variants: the Authoritarian OS, which creates people-pleasers terrified of disapproval; the Permissive OS, which produces adults addicted to external validation; and the Inconsistent OS, which generates shapeshifters who adapt to every environment but possess no stable core.

I recognized myself immediately in the third category. My parents were loving but chaotic—artists who moved us eleven times before I turned sixteen, whose affection arrived unpredictably and whose attention wandered according to the demands of their creative lives. I learned early to read rooms and become whatever version of myself would generate the least friction. This skill served me well in my career. It also meant that at fifty-four, I could not answer the simple question of what I actually wanted from my life. I had been so busy adapting to external circumstances that I had never developed preferences of my own.

Chapter Two expands the lens from personal programming to collective manipulation. Taylor walks the reader through historical case studies—the Nayirah testimony that helped launch the Gulf War, Edward Bernays's campaign to overthrow Guatemala's government on behalf of the United Fruit Company, the Pentagon's documented influence over Hollywood scripts. The chapter's purpose is to demonstrate a simple principle: if you do not understand how influence operates, you will be subject to it without knowing. The reader is given a diagnostic question to carry forward: "What am I being made to feel, and why now?" I have asked myself this question perhaps a thousand times since reading that chapter. It has changed how I consume news, how I interpret advertisements, and how I listen to politicians. It is a small tool that produces large effects.

Chapter Three concerns what Taylor calls "The Contract"—the implicit agreement we make to surrender autonomy in exchange for social approval and safety. He draws on Milgram's obedience experiments, Seligman's research on learned helplessness, and Sartre's concept of "bad faith" to argue that most people have voluntarily imprisoned themselves. The chapter is relentless. It offers no comfort. By its end, I understood that I had spent my entire adult life trading authenticity for the approval of editors, readers, and romantic partners who were themselves trading their authenticity for approval from others. We were all performing for audiences who were too busy performing to watch.

The diagnosis is unpleasant. The implication—that you have been complicit in your own captivity—is difficult to accept. Taylor knows this. He addresses it directly, noting that the rage and discomfort produced by Part I are necessary fuel for what follows. He is not wrong, though I wished at the time that he were.

Part II: The Reconstruction

The heart of the book is Part II, a three-chapter sequence Taylor calls "The Chrysalis." It contains the protocols that transform diagnosis into change. Without completing this section, the influence frameworks that follow become, in Taylor's words, "weapons handed to children." I did not understand this warning until I tried to skip ahead.

Chapter Four introduces the "21-Day Empathy Protocol," a structured practice for rewiring how you listen, perceive, and relate to others. Taylor argues that what most people call empathy is actually a form of emotional hemorrhaging—absorbing others' feelings until you cannot distinguish their pain from your own. The alternative he proposes is what he calls the "Marble Statue": the capacity to understand completely while remaining emotionally sovereign. The metaphor is drawn from Stoic philosophy. The practice is drawn from neuroscience and ancient contemplative traditions.

I will be honest: the 21-Day Protocol was the most difficult thing I have done in my adult life. The first week requires documenting every instance in which you "bleed" (absorb others' emotions) or "feed" (inject your own experience into their narrative). I discovered that I did both constantly. I could not have a conversation without relating the other person's experience to my own. I could not listen to someone's difficulty without feeling it in my chest for hours afterward. I had believed these tendencies made me a good writer, a sensitive observer of human experience. Taylor's framework revealed them as sophisticated forms of narcissism and boundary failure.

The second week introduces perceptual training: reading micro-expressions, mapping emotional territories, analyzing linguistic patterns. I practiced these skills on strangers in coffee shops, on family members during holiday gatherings, and on old friends who did not know they were being observed. The experience was disorienting. I began to see layers in conversations I had previously experienced as flat. I noticed the gap between what people said and what their bodies communicated. I watched my own patterns with a clarity that was, at times, unbearable.

The third week concerns integration and ethics. Taylor is explicit that the perceptual abilities developed in the protocol carry moral weight. He introduces what he calls the "Three-Gate Test" for any influence attempt: Is it truthful? Is it respectful? Is it necessary and beneficial? The chapter also addresses the risk of becoming cold, of using understanding as a weapon, of sliding into the narcissistic patterns the book ostensibly opposes. This self-awareness about the material's dangers is, I think, what separates Taylor's work from the manipulation manuals it superficially resembles.

Chapter Five, "The Parasite," names the internal voice of self-sabotage and provides protocols for its elimination. Taylor's language here is violent—he speaks of "killing" the parasite through "sacred violence"—but the substance is psychological rather than mystical. The chapter identifies common variants of the inner critic (The Perfectionist, The Imposter, The Scarcity Voice) and provides specific exercises for confronting each. The central mechanism is what Taylor calls a "Guillotine": an immediate, irreversible action that proves you are done standing at thresholds. I sent an email I had been avoiding for three years. The response was not what I feared. The parasite had been lying.

Chapter Six, "The Naked King," contains the "72-Hour Phoenix Protocol"—an intensive psychological reset that Taylor compares to Navy SEAL Hell Week. I will not describe the protocol in detail because doing so would diminish its impact. I will say only that I emerged from those three days different. Not transformed in some dramatic, cinematic way. But the internal weather had shifted. The voice that had narrated my failures for decades was quieter. The space it left behind felt strange, like a room after the furniture has been removed. I am still learning how to furnish it.

Parts III, IV, and V: The Frameworks

The remaining chapters cover influence, power dynamics, and ethics. Chapter Seven maps the "Ten Hungers" that drive human behavior. Chapter Eight explains the mechanics of psychological bonding. Chapter Nine provides a taxonomy of cognitive biases and how to deploy them. Chapter Eleven—Taylor calls it "The Serpent's Tongue"—details linguistic patterns that bypass conscious resistance. Chapter Twelve teaches narrative construction for psychological effect.

These chapters are where the book's title makes sense. They are also where the material becomes genuinely dangerous in untrained hands. Taylor is teaching manipulation. He is explicit about this. His argument is that these techniques are already being used on you by advertisers, politicians, and intimate partners who may not have your interests at heart. Learning them is defensive as much as offensive.

I have used the frameworks sparingly, like in a negotiation with a publication that had underpaid me for years and a conversation with my adult son about patterns in our relationship that we had never named. In both cases, the tools worked. In both cases, I felt the temptation to push further than was ethical. The Part II work—the sovereignty, the self-awareness—was what allowed me to stop.

This is why the book's structure matters. Without the internal reconstruction, the influence frameworks become manipulation without conscience. With it, they become instruments of clarity that can be used for genuine good. Taylor's gamble is that readers will complete Part II before reaching Part III. Based on the online community that has formed around the book, most serious readers do. Those who skip ahead tend to bounce off the material or use it clumsily. The protocols are load-bearing.

For Whom Is This Book Written?

I have thought carefully about who should read this book and who should not.

It is written for the person who has tried therapy, self-help seminars, meditation retreats, and found that none of it produced lasting change. Taylor's framework explains why: those modalities often validate the self that needs to die rather than killing it. The book offers something harsher and, in my experience, more effective.

It is written for the person who suspects they have been living according to someone else's script—a parent's expectations, a culture's definition of success, a partner's needs—and wants to discover what they actually want. Part I provides the diagnosis. Part II provides the reconstruction.

It is written for the person who works in any field involving influence—sales, marketing, leadership, therapy, education—and wants to understand the mechanics of what they do. The frameworks are sophisticated and evidence-based. They will make you better at your work. They may also make you question whether your work serves the good.

It is perhaps not written for the person who wants gentle encouragement. Taylor's voice is confrontational by design. He believes that comfort perpetuates captivity. If you need warmth and validation, this is not your book. If you need someone to tell you hard truths in language that does not soften the blow, it may be exactly what you require.

It is also not written for the person who wants quick fixes. The protocols require time and genuine effort. Part II alone demands nearly a month of daily practice. The results compound, but they do not arrive overnight.

A Note on Authenticity

I should address the author's anonymity. Stan Taylor is a pen name. There is no author photograph, biography, or social media presence beyond the accounts promoting the book. Taylor has stated that this is deliberate—partly for safety, partly to prevent what he calls "narcissistic collapse," and partly to keep readers focused on the work rather than the person.

I was initially skeptical of this choice. It seemed like a marketing gimmick or an evasion of accountability. Having completed the book and participated in the reader community, I have revised this judgment. The anonymity functions as the author intended because it prevents the parasitic attachment that forms around visible gurus. There is no face to idealize or reject. There is only the material and whether it works when you apply it.

On that measure, I can only report my own experience. The material works. Not perfectly, not without difficulty, but substantially and durably. I am not the same person who sat in that Holiday Inn a couple of months ago. The changes are not dramatic from the outside—I still write, travel, and struggle with the same chronic back pain and preference for solitude. But the mind is different. I make decisions from somewhere more solid. I understand my own patterns well enough to interrupt them. I see other people more clearly and with more compassion because I am no longer drowning in their emotional weather.

I must also mention something practical. Since the book's success, imitations have appeared on Amazon with similar titles and covers. These are not affiliated with Taylor. They are opportunistic knockoffs produced by publishers who recognized a market and moved to exploit it. If you search for the book, you will find these counterfeits ranked high. The legitimate version is available only through the author's website.

This small grift is, in its way, a validation of the book's thesis. Systems exist to extract value from your attention and money. People will manipulate your desire for transformation to serve their own ends. The question is whether you will see these patterns clearly enough to navigate them—or whether you will remain, as Taylor puts it, "a walking dead person living someone else's script."

I know which I prefer. The choice, as always, is yours.

Tobi Miles is a University of Florida graduate turned globe-trotting culinary explorer and digital nomad expert. As the founder of "Bytes & Bites," he combines his passion for international cuisine with practical advice on remote work, inspiring others to experience the world through food and cultural immersion. With 32 countries under his belt and a knack for uncovering hidden culinary gems, Tobi is redefining the intersection of work, travel, and gastronomy for a new generation of adventurers.